Featured Stories, MIT, News | July 27, 2016

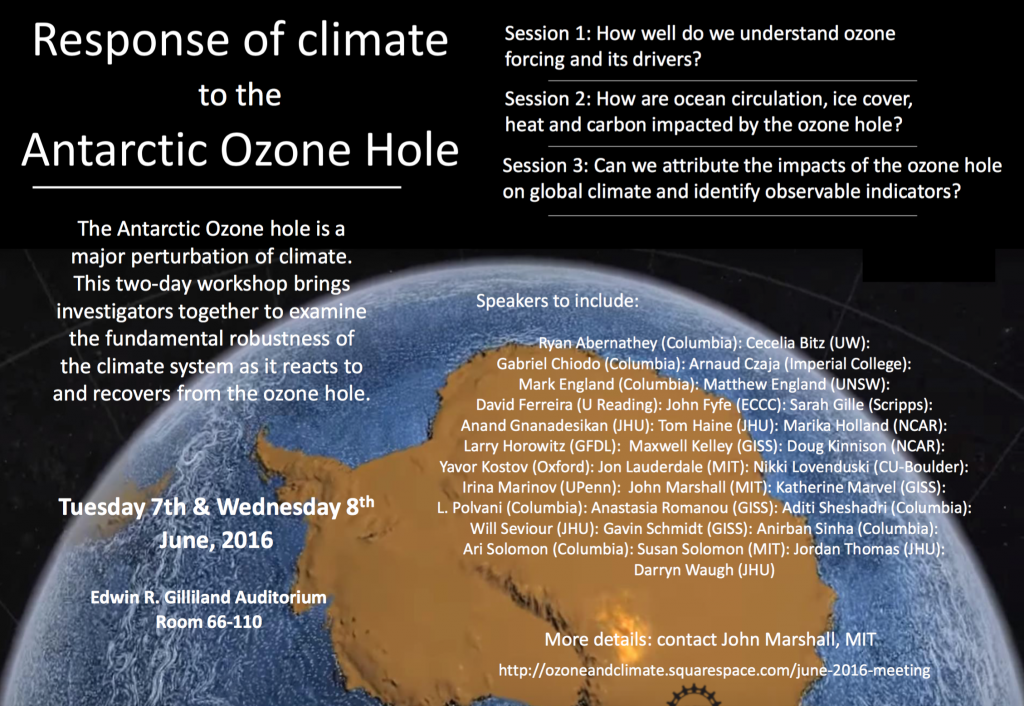

The Third Annual Meeting of the Ozone and Climate Project

On June 7-8th, 2016, oceanographers, marine biogeochemists, atmospheric scientists and climatologists from across the world converged on MIT for the third annual meeting of the Ozone and Climate Project in the Edwin Gilliland Auditorium.

The five-year project aims to understand the Antarctic ozone hole’s impact on Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, and its importance in the global picture of climate change. Overall, researchers agree that this region plays a key role in heat and carbon exchange between the atmosphere and ocean. Here, the ocean upwells cold, carbon-rich water from the deep, as well as takes up heat and CO2 from the atmosphere. But it is still unclear how the ozone hole has perturbed these processes. This study, funded by the NSF’s Frontiers in Earth System Dynamics program (FESD), explores—through observations, theory and modeling—the climate system’s response to ozone depletion and how it has adjusted as the Earth’s protective stratospheric layer heals.

This year, thirty select project members and invited guests led informal and open discussions with the goal of exploring two primary questions: What are the climate impacts of stratospheric ozone depletion and recovery over the Antarctic? And, what are the indicators and mechanisms of these impacts within this atmosphere-ocean-ice-carbon system?

The group organized the discussion around three main themes:

- How does interactive chemistry modify coupling between the stratospheric vortex and the rest of the climate system?

- How are ocean circulation, ice cover, heat and carbon uptake and biogeochemistry impacted by the ozone hole?

- How does the ozone hole impact global climate and what are the observable indicators?

Project investigator and MIT Atmospheric Chemist Susan Solomon recently led a study documenting the Montreal Protocol’s efficacy in curtailing the emission of ozone-destroying chemicals, which is helping to heal the ozone hole. Indeed, “the view out there [with the public] is that the ozone hole problem has been solved,” said John Marshall, the project’s principle investigator and an MIT oceanographer. “But we’re learning a lot about the climate system by observing how it adjusts to the healing of the ozone hole. So I think that’s an important thing to bring out and the other big context is: What’s going on around Antarctica in general?”

Many of the researchers in attendance like Solomon, Darryn Waugh and Lorenzo Polvani have been working together on this and similar ozone issues for decades, so there was a healthy dialogue amongst them. One topic that kept being raised during the conference was the need to “get ozone right” in the models i.e. the correct atmospheric response to changes in its concentration and location. “Ozone is a tough thing to deal with in the climate models. A distribution can be prescribed from data for recent years, but we have limited observations prior to 1986,” said Solomon. As the ozone hole develops, the polar vortex cools and strengthens, causing dynamical changes in the stratosphere like SAM (Southern Annual Mode, which helps to drive the strength and position of the Westerly winds circling around Antarctica) and the Jetstream position and strength. But as Solomon explained during the conference, the polar vortex moves around, which isn’t simulated in a couple of the frequently-used models, but, “simply prescribing ozone from data, whether zonally averaged or not, means that the polar vortex in the model will not be in the same place as the polar vortex as the data.” While there is the option to incorporate interactive chemistry into the models, so that everything’s consistent, there are cost and time trade-offs. “It’s an ongoing question how much of a problem that is, and what to do about it,” she said.

Other members like Marshall and Yavor Kostov, a postdoc at Oxford and recent MIT PhD graduate, were among several those whose work addressed the ocean-sea ice relationship in the context of ozone forcing. Kostov proposed that under ozone depletion and an increase in SAM with its associated winds, ocean surface temperatures cool, which could be responsible for sea ice expansion around Antarctica, in general. Some, like Marika Holland of NCAR, emphasized the importance of specific regions, such as ice cover in the Ross Sea.

Another area of research that the group is contributing to is heat and carbon uptake as well as biogeochemical impacts in the Antarctic region that could be affected by the ozone hole. Groups from Johns Hopkins, the University of Reading, CU-Boulder and MIT, in particular, focused on these aspects. One of the questions addressed was whether the Southern Ocean is a sink of anthropogenic carbon or not. Jon Lauderdale, an MIT postdoc in oceanography, spoke about how one quantifies competing mechanisms that affect air-sea carbon fluxes. Some investigators have found that the strength of this sink may have been weakening, but is now recovering. This may be due to effects from the ozone hole or potentially natural variability. However, several presentations like Anand Gnanadesikan’s, Nikki Lovenduski’s and David Ferreira’s, showed that the ozone hole had little net impact on carbon uptake.

Take-Aways and Final Impressions:

Discussions throughout the FESD conference were lively and, while there is still much research left to do, many felt optimistic for the future of research surrounding the ozone hole and the Antarctic region. “I think it’s a really exciting time to be in Southern Ocean science because you’ve got high-powered models, that are getting better and are free,” Lauderdale said. “Free, meaning, you’re actually simulating the things you want to simulate, rather than parameterizing or imposing them, like interactive chemistry and the biogeochemical cycles.” Additionally, more ARGO floats are coming online with abilities for biogeochemical sensing and floats that can stay under the sea ice, getting readings in areas and seasons that were previously unattainable. “We’re just collecting so much more data, so much more regularly and with more extensive coverage in unusual places. [With this], I think we’ll get a very good idea for what the baseline is,” he said.

MIT’s Susan Solomon was encouraged by the progress made by the project, and plans to incorporate some of the issues raised by Ozone and Climate Project attendees into her own future research. “I thought the workshop was very stimulating—lots of diverse ideas from people at a range of institutions always bring out the best in science.”

****

Read more about the presenters’ work here.