Featured Stories, MIT, WHOI | April 5, 2013

Sparks Fly as Art and Science Collide in “Ocean Stories”: A Review

By Genevieve Wanucha

In the space of fifteen minutes, three different parents have had to pull their curious children back from an oil painting at Boston’s Museum of Science. It’s too late for that. A little girl in a pink jacket rushes up and runs her hand across a swirl of peach paint, as her mother cries, “Don’t touch!” I, too, wouldn’t mind getting closer to artist Bryan McFarlane’s colorful rendering of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These chimneys in the ocean floor erupt with boiling, mineral-rich fluids, providing bizarre organisms with energy where sunlight doesn’t reach.

Like all the art works displayed in the “Oceans Stories” exhibit, McFarlane’s painting reinterprets the research of ocean scientists from MIT or Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. The inky darkness alive with bright orbs and strange aquatic shapes envisions the underworld that chemical oceanographer Jill McDermott scours by the dim light of a submarine, part of how she studies the chemical reactions sustaining benthos in extreme temperatures and pressure. In his painting, as in her research, treasures hide in plain view.

“Ocean Stories” is a production of Synergy, a newly formed experimental organization aiming to stimulate a “collision of art and science.” Executive director Whitney Bernstein, an oceanographer working towards her PhD from the WHOI/MIT Joint Program, says the idea for the project stemmed from a desire to communicate scientific issues to a wider audience. “I’m struck by the ability of art to convey expansive ideas in a concise way,” she says. “It gets to the heart of the story and can tell it in a visceral way.” She wasted no time turning the “spark in her brain” into Synergy’s first project.

In 2012, Bernstein, along with co-director Lizzie Kripke and program coordinator Michael MacCohen, paired professional artists with eight ocean scientists from MIT and WHOI, birthing this collection of sculpture, painting, and digital media. The diversity of the finished products was unplanned and unprompted.

If you walk clockwise around the exhibit room, the first work you’ll see is a photo collage of healthy, vibrant coral reef ecosystems and barren, bleached lifeless coral skeleton, the result of a collaboration between artist Joseph Ingoldsby and oceanographers Katie Shamberger, Hannah Barkley and Alice Alpert. It’s an unambiguous introduction to the uncomfortable reality that human activity damages ocean life in very tangible ways. Scientists have the job of closing the big gap between knowing there’s a crisis and understanding exactly how the ocean is changing, chemically, thermally, physically. At least for me, the images peak a curiosity about the research explored through the rest of the exhibit.

More ocean-floor science was to be visited: Laurie Kaplowitz’s mixed-media drawings are inspired by biological oceanographer Ellie Bors, who uses the DNA of deep-sea animals in order to understand how different species are evolutionarily related to one another. One very tall monochromatic drawing uses actual words lifted from Bors’ daily lab notebook. These inscriptions are written over and over each other, forming a chalk-dusty cloud billowing upwards against the pitch black. While I strain my eyes trying to make out individual phrases, I realize that Kaplowitz has exactly mirrored the experience of a scientist questing to decipher the mysterious biological and genetic messages floating in these deep-sea vents.

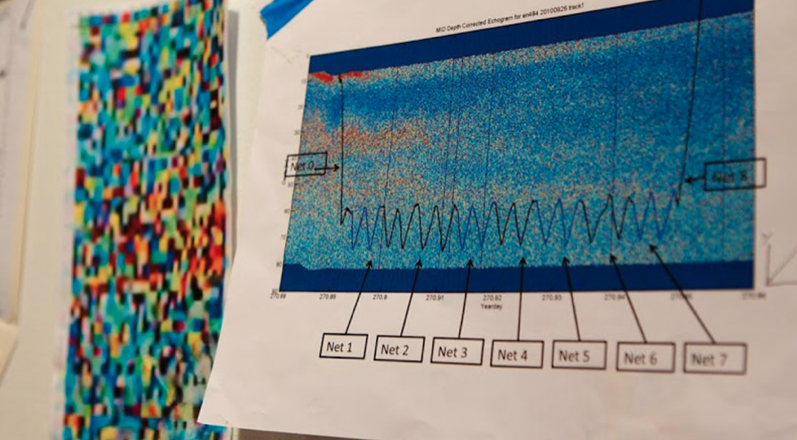

In the center of the room stands one of the most cognitively demanding works of art: Nathalie Miebach’s enormous wood and rope sculpture of carnival rides–a Ferris Wheel, roller coaster, and merry-go-round that incorporate the unusual art medium of actual data. Meibach collaborated with Jonathan Fincke, an ocean engineer who wants to understand how climate change affects ocean productivity. He uses acoustic techniques to measure sound that echoes off the tiny bodies of zooplankton, which allows him to track the distribution and behavior of a critical member of the food web.

Little pink origami shrimp are stuck into the Ferris wheel’s spokes. I don’t understand why until I read that Meibach literally used Fincke’s acoustic data to illustrate the presence of krill, a type of zooplankton, in the water near Georges Bank, Maine, over time. For example, the merry-go-round depicts how krill data vary with air and water temperature, salinity, current, wave height, and sun’s angle. The longer you look back and forth from the sculpture to the written explanation accompanying “To Hear the Ocean in a Whisper, the more patterns you see.

Some people take time to read the text. Some peer into the twisting structure and wander away. Everyone says, “Wow!” as they look.

My personal favorite grapples with the issue motivating oceanographer Sophie Chu. It’s a simple concentric arrangement of 350 eggshells. The shells’ surfaces, however, warp and melt, having been deformed by acid. The connection to science is direct. The ocean absorbs up to a third of the carbon dioxide released by human activity. As a result, the ocean is becoming more acidic, inhibiting the ability of corals and other organisms to make their shells. The eggshells in artist Karen Ristuben’s work stand in for pteropods, or sea snails, who are especially vulnerable to ocean acidification. It’s disturbing, striking, and concise. Ugly damage to the delicate geometry of Nature. “It gets to the heart of ocean acidification,” says Bernstein. “It hurts shells–but pteropods are tiny, so why should we care? Well, they are numerous, and they are a critical food for fish.”

There are plenty more art works at the exhibit than I can mention here, including a poem-lithograph fusion that provides a better, more accessible explanation of the ocean’s carbon cycle that I have ever read, ever; the spectacular physics of ocean eddies embodied in intricately hand-dyed fishing line; and slow-motion computer-generated abstractions representing the endangered relationship between coastal eelgrass habitats and sunlight.

Bernstein and her team have yet to evaluate whether the public is actually engaging with science, whether they leave the room driven to learn more about marine issues. But I can see some positive signs. On her way out of the exhibit, Boston resident Tegan Mortimer reports, “It’s a fascinating way to view the ocean—through the eye of an artist,” she says. “It’s more than looking at a photo. The art provides emotion and gives a new way of seeing the current problems.” It’s true. For all the practical differences, science and art are natural partners. Ocean research brings us to faraway places, sometimes all the way down to the seafloor; Art reaches the short distance inside us by the instantaneity of emotion reaction. Artistic expression of the scientific process, therefore, collapses the long miles that can lie between ocean discovery and the public’s attention. And that’s, well, true synergy.

“Ocean Stories” is on display until June 2.