Engineers at MIT have fabricated transparent, gel-based robots that move when water is pumped in and out of them. The bots can perform a number of fast, forceful tasks, including kicking a ball underwater, and grabbing and releasing a live fish.

The robots are made entirely of hydrogel — a tough, rubbery, nearly transparent material that’s composed mostly of water. Each robot is an assemblage of hollow, precisely designed hydrogel structures, connected to rubbery tubes. When the researchers pump water into the hydrogel robots, the structures quickly inflate in orientations that enable the bots to curl up or stretch out.

The team fashioned several hydrogel robots, including a finlike structure that flaps back and forth, an articulated appendage that makes kicking motions, and a soft, hand-shaped robot that can squeeze and relax.

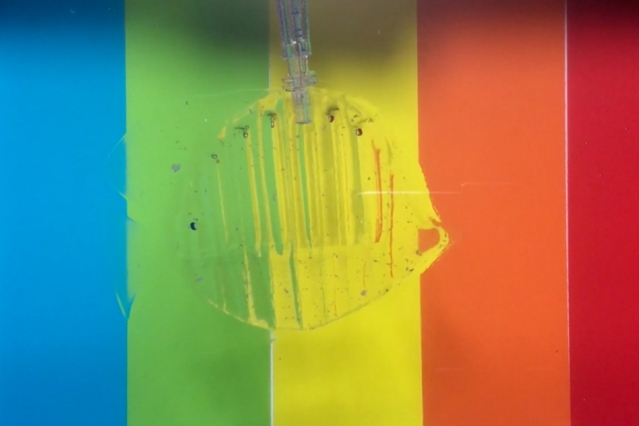

Because the robots are both powered by and made almost entirely of water, they have similar visual and acoustic properties to water. The researchers propose that these robots, if designed for underwater applications, may be virtually invisible.

Engineers at MIT have fabricated transparent gel robots that can perform a number of fast, forceful tasks, including kicking a ball underwater, and grabbing and releasing a live fish. (Video: Melanie Gonick/MIT)

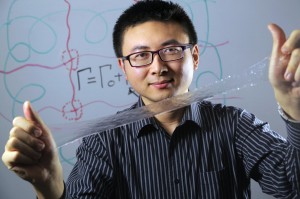

The group, led by Xuanhe Zhao, associate professor of mechanical engineering and civil and environmental engineering at MIT, and graduate student Hyunwoo Yuk, is currently looking to adapt hydrogel robots for medical applications.

“Hydrogels are soft, wet, biocompatible, and can form more friendly interfaces with human organs,” Zhao says. “We are actively collaborating with medical groups to translate this system into soft manipulators such as hydrogel ‘hands,’ which could potentially apply more gentle manipulations to tissues and organs in surgical operations.”

Zhao and Yuk have published their results this week in the journal Nature Communications. Their co-authors include MIT graduate students Shaoting Lin and Chu Ma, postdoc Mahdi Takaffoli, and associate professor of mechanical engineering Nicholas X. Fang.

Robot recipe

For the past five years, Zhao’s group has been developing “recipes” for hydrogels, mixing solutions of polymers and water, and using techniques they invented to fabricate tough yet highly stretchable materials. They have also developed ways to glue these hydrogels to various surfaces such as glass, metal, ceramic, and rubber, creating extremely strong bonds that resist peeling.

The team realized that such durable, flexible, strongly bondable hydrogels might be ideal materials for use in soft robotics. Many groups have designed soft robots from rubbers like silicones, but Zhao points out that such materials are not as biocompatible as hydrogels. As hydrogels are mostly composed of water, he says, they are naturally safer to use in a biomedical setting. And while others have attempted to fashion robots out of hydrogels, their solutions have resulted in brittle, relatively inflexible materials that crack or burst with repeated use.

In contrast, Zhao’s group found its formulations leant themselves well to soft robotics.

“We didn’t think of this kind of [soft robotics] project initially, but realized maybe our expertise can be crucial to translating these jellies as robust actuators and robotic structures,” Yuk says.

Fast and forceful

To apply their hydrogel materials to soft robotics, the researchers first looked to the animal world. They concentrated in particular on leptocephali, or glass eels — tiny, transparent, hydrogel-like eel larvae that hatch in the ocean and eventually migrate to their natural river habitats.

“It is extremely long travel, and there is no means of protection,” Yuk says. “It seems they tried to evolve into a transparent form as an efficient camouflage tactic. And we wanted to achieve a similar level of transparency, force, and speed.”

To do so, Yuk and Zhao used 3-D printing and laser cutting techniques to print their hydrogel recipes into robotic structures and other hollow units, which they bonded to small, rubbery tubes that are connected to external pumps.

To actuate, or move, the structures, the team used syringe pumps to inject water through the hollow structures, enabling them to quickly curl or stretch, depending on the overall configuration of the robots.

Yuk and Zhao found that by pumping water in, they could produce fast, forceful reactions, enabling a hydrogel robot to generate a few newtons of force in one second. For perspective, other researchers have activated similar hydrogel robots by simple osmosis, letting water naturally seep into structures — a slow process that creates millinewton forces over several minutes or hours.

Catch and release

In experiments using several hydrogel robot designs, the team found the structures were able to withstand repeated use of up to 1,000 cycles without rupturing or tearing. They also found that each design, placed underwater against colored backgrounds, appeared almost entirely camouflaged. The group measured the acoustic and optical properties of the hydrogel robots, and found them to be nearly equal to that of water, unlike rubber and other commonly used materials in soft robotics.

In a striking demonstration of the technology, the team fabricated a hand-like robotic gripper and pumped water in and out of its “fingers” to make the hand open and close. The researchers submerged the gripper in a tank with a goldfish and showed that as the fish swam past, the gripper was strong and fast enough to close around the fish.

“[The robot] is almost transparent, very hard to see,” Zhao says. “When you release the fish, it’s quite happy because [the robot] is soft and doesn’t damage the fish. Imagine a hard robotic hand would probably squash the fish.”

Next, the researchers plan to identify specific applications for hydrogel robotics, as well as tailor their recipes to particular uses. For example, medical applications might not require completely transparent structures, while other applications may need certain parts of a robot to be stiffer than others.

“We want to pinpoint a realistic application and optimize the material to achieve something impactful,” Yuk says. “To our best knowledge, this is the first demonstration of hydrogel pressure-based acutuation. We are now tossing this concept out as an open question, to say, ‘Let’s play with this.’”

This research was supported, in part, by the Office of Naval Research, the MIT Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, and the National Science Foundation.